Contact center of the Ukrainian Judiciary 044 207-35-46

The issue was discussed at the roundtable on "Mechanisms for Judicial Protection of Children from Domestic Violence", which brought together judges of the Supreme Court, appellate and local courts, the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights, the Commissioner for the European Court of Human Rights, representatives of the Prosecutor General's Office, the Juvenile Prevention Department of the National Police of Ukraine, social services and children's services, and the public.

After the welcoming speeches, three sessions of the event took place, moderated by Olha Stupak, Judge of the Supreme Court of the Civil Cassation Court, and Mariia Borodiichuk, Head of the NGO Prevent.

Serhii Pohribnyi, a judge of the Supreme Court in the Civil Cassation Court, stressed that the court cannot replace law enforcement agencies, but that the two are partners with a common goal of ensuring the rule of law. He also emphasised that the Supreme Court has repeatedly stated in its decisions that the best interests of the child should take precedence in disputes involving children, and that the rights of the parents should take a back seat.

"The court should always assess whether the interests of each parent are in line with the interests of the child, and only then make a decision in favour of one of them," said Serhii Pohribnyi.

He noted that the war had further highlighted the inadequacies of the family legislation inherited from the Soviet system. Modern international law is more comprehensive and includes rules on child custody, i.e. not only who the child will live with, but also issues relating to the child's development, education, etc.

The speaker analysed the jurisprudence of the Civil Cassation Court of the Supreme Court on the jurisdiction of national courts to resolve disputes on the return to Ukraine of children, in particular those who were taken to other countries after 24 February 2024. "These decisions are, in fact, a guide for the courts in resolving the jurisdictional issues of the national courts in the relevant disputes," said Serhii Pohribnyi.

For Ukrainian courts to have jurisdiction in such cases, it is necessary to establish the child's "habitual residence" in Ukraine during the period before the child was illegally removed to another country (with certain exceptions). The speaker emphasised that to determine the child's habitual residence, it is not enough to take into account his or her citizenship or registration of residence. When applying to the court, the plaintiff must prove that the child actually lived in a certain place: attended school, received medical care, had social ties, etc.

The court must then determine whether the national court has lost jurisdiction because the child has chosen another habitual residence, in particular because the child has been living elsewhere for a long time and the parent not living with the child does not take steps to return the child. Even if a child has refugee status or moves to another country, the Ukrainian court remains competent to decide on his or her return.

Olena Bilokon, Judge of the Supreme Court at the Civil Cassation Court spoke about the practice of using restraining orders as one of the tools to prevent and combat domestic violence, which can harm children who have experienced or witnessed any form of domestic violence.

Ukraine has ratified the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. This means that the state has recognised that domestic violence is not a problem for the individual family, which should be solved exclusively within the family at its own discretion, and that it is the state that should provide effective protection against domestic violence. As part of the preparations for ratification of the Convention, Law of Ukraine No. 2229-VIII of 7 December 2017 "On Preventing and Combating Domestic Violence" was adopted, which amended the Civil Procedure Code of Ukraine to provide for court consideration of cases on the application of restraining orders against perpetrators.

The judge noted that this category of cases raised many controversial issues. This is due to the novelty of these cases, as well as difficulties in assessing the factual data on domestic violence, short timeframes for considering the cases, emotional stress during the proceedings, etc.

In the five years that the courts have been applying the restraining orders, the Supreme Court has developed a certain practice and a set of legal positions. In 2021, the Civil Cassation Court of the Supreme Court published the Review of the Practice of Issuing Restraining Orders. At the event, Olena Bilokon analysed the 2022-2023 judicial practices, considering its formation during the war.

In order to facilitate access to judicial protection for victims of domestic violence, a number of specific features have been established for the examination of applications for restraining orders. These procedures provide for preferential jurisdiction, exemption from court fees, a wider range of applicants, a shorter review period (72 hours), which may be conducted without the participation of the applicant in the event of a threat of violence, and immediate enforcement of a court decision to issue a restraining order.

In cases of domestic violence against a child, one of the parents (usually the mother against the father) is most often the complainant. It is already common practice for courts to consider applications from other relatives of children or from the guardianship and custody authority. There are cases in which the application for a restraining order was filed by the child himself or herself through a lawyer provided by Free Legal Aid.

Olena Bilokon stressed that a restraining order is not a punishment, as is sometimes believed by the general public. In one of its resolutions, the Civil Cassation Court of the Supreme Court stated that a restraining order is not a punitive but rather a temporary measure with a protective and preventive function aimed at preventing violence and ensuring the primary safety of the victims until the issue of bringing the perpetrator to administrative or criminal liability is resolved. The judge noted that several restrictive orders could be applied to an offender at the same time, pointed out that only those prescribed by law could be applied (such as an eviction order could not be applied), etc.

The speaker also cited the Supreme Court's case law on the grounds for using restraining orders in cases of violence against children and the specifics of proof in such cases. She also focused on the distinction between family conflict and domestic violence through the prism of judicial consideration of applications for the grant and extension of restraining orders.

Yevhen Synelnykov, Judge of the Supreme Court at the Civil Cassation Court, spoke about the application by the courts of the provisions of Article 162 of the Family Code of Ukraine, which defines the legal tools for responding to the unauthorised change of a child's place of residence by one of the parents. The provisions of this article are designed to protect the rights and interests of the child, and therefore it is necessary to identify and assess the positive outcome for the child's future in each case, taking into account the interests of the parents.

Yevhen Synelnykov noted that, according to the content of the article in question, the child can only be taken away if there is an agreement between the parents or a court decision determining the child's place of residence.

The question also arises as to the urgency of the decision to remove the child and return him or her to his or her former place of residence. The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child has repeatedly stated that cases involving children should be prioritised and heard without delay. In its judgments, the ECtHR held that lengthy proceedings against children were a violation of Article 8 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (Case M. and M. v. Croatia, Application No. 10161/13).

The national judicial system of Ukraine faces the following challenges, among others: lack of staff, lack of (insufficient) specialisation of judges (courts) in family disputes, enforcement of court decisions concerning children and the efficiency of children's affairs agencies, which affect the timeframe for considering relevant cases.

Yevhen Synelnykov drew attention to the need to take into account the interests of the child, to seek the child's opinion in cases involving children, with reference to international practice; he pointed out that, under certain conditions, the child may be left at the previous place of residence; he referred to the practice of the Supreme Court on compensation for non-pecuniary damage for abduction of a child.

The speaker emphasised that disputes between parents over a child should be resolved not only by establishing the child's place of residence with one of the parents. Worldwide judicial practice has confirmed the expediency of establishing mutual physical custody (control and care) of the parents, whereby the child lives with the father for a certain period of time and with the mother for a certain period of time, and both parents are actively involved in the child's development and upbringing. This reduces or eliminates the element of confrontation between the parents, establishes cooperation between them and ensures the best interests of the child, who loves both parents and needs care and education from each.

The head of the National Social Service of Ukraine, Vasyl Lutsyk, said that the Service, in particular, deals with the return of children from abroad to Ukraine or with problems that arise in other countries regarding Ukrainian children. The Service oversees over 400 cases, each potentially involving several children. The number of such applications is growing and will continue to do so. Some cases concern the removal of children from their parents or legal guardians abroad. Other countries react harshly to domestic violence: they can deport the parents and leave the child behind, etc. The assistance of the Ukrainian courts is important here because a number of countries do not recognise the powers of legal representatives established by a decision of the guardianship and custody authority; these countries recognise only the powers established by a court decision. Such decisions must be received within a short time.

Vasyl Lutsyk also raised the issue of recognising a child who witnessed violence as a victim. He noted that in many reports on violence between parents, the police do not identify the child as a victim, so the child cannot be protected. In addition, he said, the number of children who have become victims of human trafficking is increasing.

Marharyta Sokorenko, Commissioner for the European Court of Human Rights, spoke about the ECtHR's practice in dealing with cases involving the return of children to one of their parents. In such cases, the ECtHR determines whether or not there has been a violation of Article 8 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. In a number of judgments, the Court has indicated that, although the main purpose of Article 8 of the Convention is to protect individuals against arbitrary interference by public authorities, there may be additional positive obligations to ensure effective respect for family life. In its judgments, the ECtHR has recalled the right of one of the parents to take measures to reunite with the child and the obligation of the national authorities to take such measures; that the obligation of the State is not absolute and depends on the circumstances of each case; that the question of time is important, the passage of time may have irreparable consequences for the relationship between the child and the parent who does not live with him or her; that the reasonableness of the measures should be assessed in the light of the speed with which they are implemented, including the implementation of the final court decision.

The speaker drew attention to the case of M.R. and D.R. v. Ukraine, in which the ECtHR analysed in great detail the actions of the authorities to enforce the decision of the Czech court to return the child to his father in that country, and concluded that there were no legal mechanisms for the enforcement of such a decision in Ukraine. Marharyta Sokorenko also spoke about the problems associated with the return of children from states with which no assistance agreements have been concluded (the case of Oksuzoglu v. Ukraine), the safety/return of children from the Temporary Occupied Territories/active combat zone (the case of Y.S. and O.S. v. Russia).

Iryna Halas, Vice President of the Desnianskyi District Court of Kyiv, spoke about the specifics of considering cases of administrative offences under Article 173-2 of the Code of Ukraine on Administrative Offences (domestic violence). She noted that courts were often confronted with physical, psychological and sometimes economic violence when dealing with such cases. The judge said that it was necessary to distinguish between a conflict, an argument and domestic violence. A conflict and an argument are not always a manifestation of domestic violence.

The speaker noted that during domestic violence, the child was the least protected and weakest person, as he or she cannot resist the abuser and suffers not only general but also specific consequences: developmental delays, behavioural disorders, mental and psychological disturbances.

The judge stressed that the child witness was also a victim of violence. Moreover, police authorities almost never include such children as victims in domestic violence reports.

Iryna Halas spoke about the evidence that may be available in cases under Article 173-2 of the Code of Ukraine on Administrative Offences. The most important evidence is a well-drafted report. In the majority of cases, the closure of cases was established precisely because of the shortcomings of the report. Most often, the report does not contain a description of the person's actions. Often, the police do not record witnesses' explanations in the reports, although, as a rule, the conflict was seen or heard by one of the neighbours or relatives.

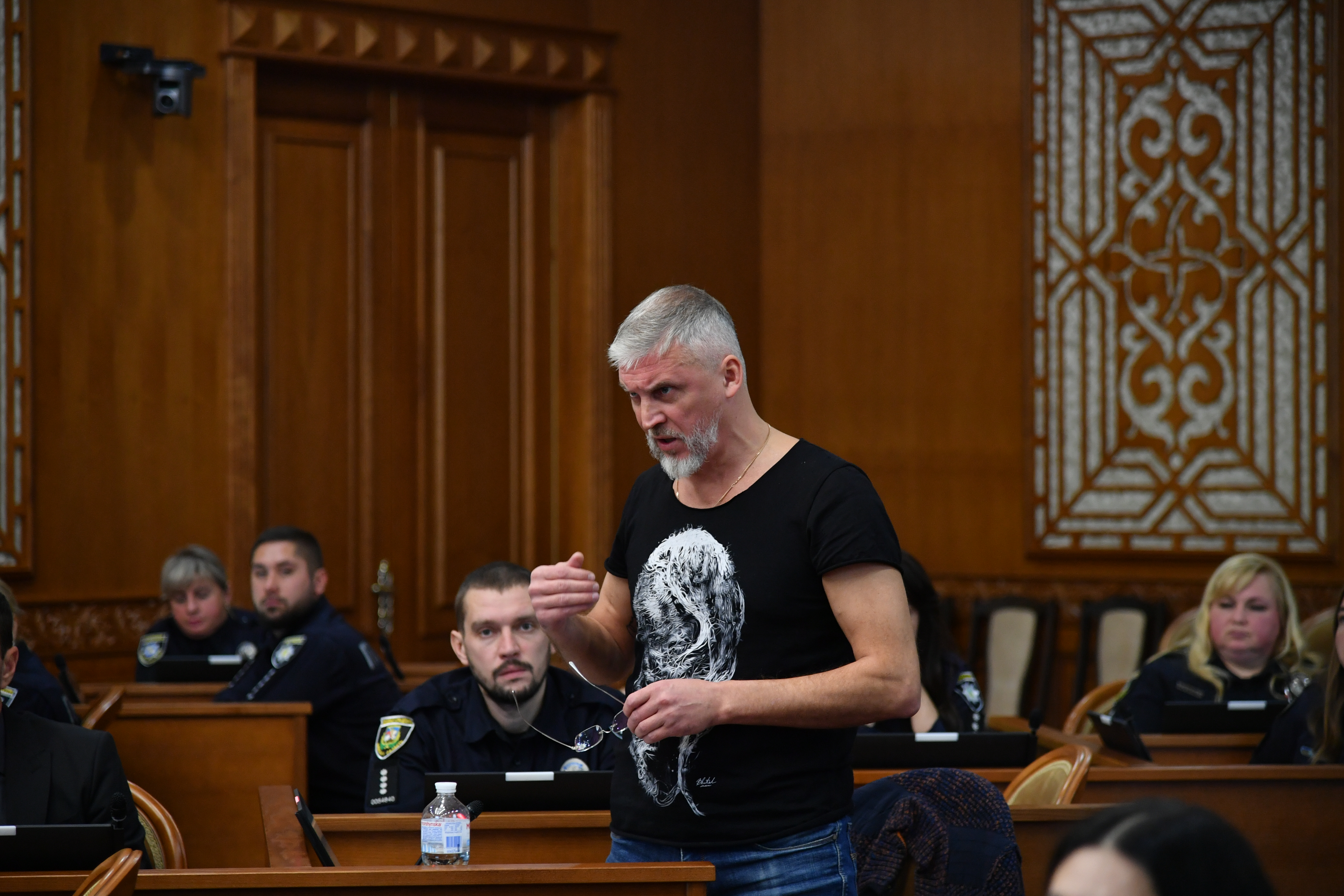

Volodymyr Borodiichuk, Vice President of the Cherkasy Court of Appeal, presented Recommendations for considering cases of administrative offences under Article 173-2 of the Code of Ukraine on Administrative Offences, which the court had developed with the support of the NGO Prevent.

He said that the court often sent the materials in such cases to the police for further processing due to certain flaws. While these materials are being sent back to the court, the time limit for prosecution expires. It appears that the police took action, the court decided the case, but the victims received no protection. Therefore, when sending materials for further processing, courts should set deadlines for their return and keep the case under control.

In addition, such closed cases often do not indicate the guilt of the person who committed the crime. The educational function of both the court and the police is thus lost. The court must therefore first establish the person's guilt and then close the case once the period of prosecution has expired.

Courts often do not summon the aggrieved party to court hearings. This has negative consequences - the court cannot consider the case objectively and the victim is deprived of the possibility to exercise his or her rights, in particular to challenge the court's decision on appeal.

According to the speaker, the issue of sentencing was actively discussed during the preparation of the Recommendations. The courts deal with the matter formally and impose a fine. But often, a fine can also be a punishment for the aggrieved party, as it is paid from the family budget.

|

|

|

|

Another very important problem, according to the speaker, is that both the police in their reports and the courts in their decisions do not identify child witnesses as victims of domestic violence.

The roundtable "Mechanisms for Judicial Protection of Children from Domestic Violence" was jointly organised by the Civil Cassation Court of the Supreme Court and the NGO Prevent.

Presentation by Serhii Pohribnyi https://is.gd/dQ5R6Q.

Presentation by Olena Bilokon - https://is.gd/a1pv65.

Presentation by Yevhen Synelnykov - https://is.gd/CenVns.

Video of the event is available at https://is.gd/T4Mykp.